The End of Third Party Cookies: Browsers Take Over Online Advertising

Here’s what that means for user privacy and your business.

Third-party cookies are being phased out by browsers and more and more limits are placed on them.

Most online analytics, advertising, and attribution tools out there are scrambling to find alternatives for collecting data. This cut back also impacts our reporting.

But understanding why browsers are limiting cookies and what are the state and country level legal frameworks is essential before looking for alternatives.

So let’s start there…

Why Do Browsers Limit Cookies?

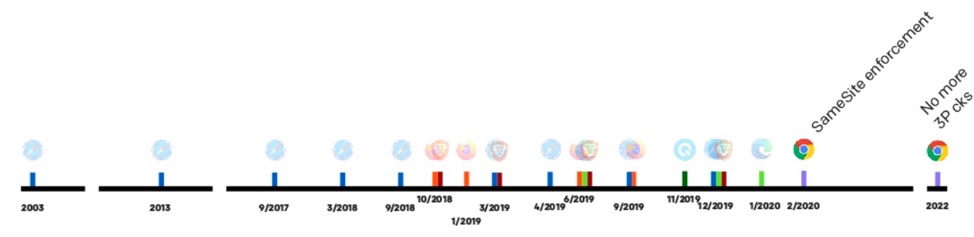

Simo Ahava’s presentation at Superweek 2020 below shows a timeline of browser changes implemented over time.

Tech products are now taking shorter steps to make changes. The enforcement rate of privacy improvement features is also picking up.

We have seen more privacy improvements in browsers in 2019 than in the 5 years leading up to it.

In my article, “Are Browsers Pushing for a Cookieless Future with Safari ITP, Firefox ETP, and Chrome Privacy Sandbox? ”, I talk at length about the reasons behind these changes:

Browsers like Safari and Firefox (and to a lesser extent, Chrome) also want to protect their users from these types of cookies, which are used to build users’ profiles and buying interests. This information will then be sold and used to target users on other sites. The ad seller will make a higher profit on an ad placement with verified intent vs on a plain ad impression. Ad industry leaders understand that the way forward is less tracking and more ad placements that match user intent on the page (by using content ad matching).

This idea comes from John Wilander who published this blog post for Webkit. According to Wilander, “Intelligent Tracking Prevention was designed to protect user privacy by preventing cross-site tracking.”

It’s all about focusing on websites building a closer relationship with their OWN users (in the context of a single site for ITP and the context of an organization for Chrome) and preventing third parties from providing this.

We strive for the blog posts to be approachable for a large audience but they need to contain enough detail to be useful for developers.

— John Wilander (@johnwilander) June 7, 2019

Is there something in particular that you’re after? Has someone recommended you read it? For a specific reason or in a specific context?

Webkit, the organization behind ITP in Safari and one of John Wilander’s projects, explains this further in their Tracking Prevention Policy:

Tracking WebKit will prevent all covert tracking, and all cross-site tracking (even when it’s not covert). These goals apply to all types of tracking listed above, as well as tracking techniques currently unknown to us. If a particular tracking technique cannot be completely prevented without undue user harm, WebKit will limit the capability of using the technique. For example, limiting the time window for tracking or reducing the available bits of entropy — unique data points that may be used to identify a user or a user’s behavior.

I don’t think a specific version of ITP is what you’re after then. Instead, think of it like this: Any JS or web platform capability that is used for cross-site tracking is or will be limited by privacy protections. …

— John Wilander (@johnwilander) June 7, 2019

Webkit knows there is an unintended side effect of their ITP project. Analytics and audience measurement in the context of a single site are not something they want to block. Analytics and A/B testing tools working to improve user experience aren’t fought against.

The issue is similar to what the new European ePrivacy Directive guidelines (updated in July 2019) and the not yet implemented ePrivacy Regulations deal with. The new rules and technologies create a legal or technological gap we cannot yet cover.

When it comes to browsers, we will hopefully get new features like isLoggedIn, Private Click Measurement and Chrome SameSite OrganizationID (First Party Sets).

But since we don’t yet have these alternatives, what are we left with? Should we ignore them like most companies do, following the ICO’s and CNIL’s updates of the ePrivacy Directive?

The European GDPR is Paving the Way for Legal Limitations

The most strict privacy law in the world is Europe’s GDPR.

The recently updated guidelines from the ICO (UK’s Privacy Authority) and the CNIL (France Privacy Authority) also condemn placing most cookies on user devices before active consent (and the use of tricks like “Accept All” buttons, pre-checked checkboxes or radio buttons). The guidelines, updated in July 2019, won’t be enforced until July 2020. At the same time, the ePrivacy Regulations (still in draft) have made some exclusions for cookies. These all state that A/B testing, analytics and measuring the effectiveness of ads (even testing ads) are permitted.

On 8 November 2019, the Finnish government issued a revised proposal for the ePrivacy Regulation with some amendments. In this proposal, some cookies can be placed without consent, as the latest draft of the ePrivacy Regulations (from November 2019) states in articles 8, 17aa and article 21a below:

Article 8: “Protection of end-users’ terminal equipment information, 1(d) it is necessary for web audience measuring, provided that such measurement is carried out by the provider of the information society service requested by the end-user or by a third party on behalf of one or more providers of the information society service provided that conditions laid down in Article 28, or where applicable Article 26, of Regulation (EU) 2016/679 are met. 2(c) it is necessary for the purpose of statistical counting that is limited in time and space to the extent necessary for this purpose and the data is made anonymous or erased as soon as it is no longer needed for this purpose.”

Article 17aa: “As end-users attach great value to the confidentiality of their communications, including their physical movements, such data cannot be used to determine the nature or characteristics of an end-user or to build a profile of an end-user, in order to, for example, avoid that the data is used for segmentation purposes, to monitor the behavior of a specific end-user or to draw conclusions concerning the private life of an end-user. For the same reason, the end-user must be provided with information about these processing activities taking place and given the right to object to such processing.”

Article 21a: “Cookies can also be a legitimate and useful tool, for example, in assessing the effectiveness of a delivered information society service, for example of website design and advertising or by helping to measure the numbers of end-users visiting a website, certain pages of a website or the number of end-users of an application. This is not the case, however, regarding cookies and similar identifiers used to determine the nature of who is using the site, which always requires the consent of the end-user.”

Put simply, web audience measuring using an analytics or a third-party tool does not need cookie consent. You can get stats from this data, but you cannot segment it to “draw conclusions concerning the private life of an end-user” — data needs to be anonymous.

The GDPR is opening up the space for A/B testing and personalization (with the hold-back option to measure the effectiveness of an experience) to content, ads or design. This makes me hopeful that we are on the right path to keep the powerful A/B testing solutions we now have, but focus on the effectiveness of the message and on providing better web experiences. We should condemn practices like singling out small groups or individuals and segmentation based on easily identifiable traits like gender, race, age or any personal data (as defined by the GDPR).

Both browsers and privacy laws are after the same thing. They both spearhead this movement, which means they’re even ahead of new alternative solutions. Their main goal isn’t to stop you from analyzing users (on your site) or to do A/B testing to improve and optimize user experience. They are here to prevent identities being built on third-party locations outside the single site context, without active user consent. More about this in this article I wrote.

The Future of Browsers

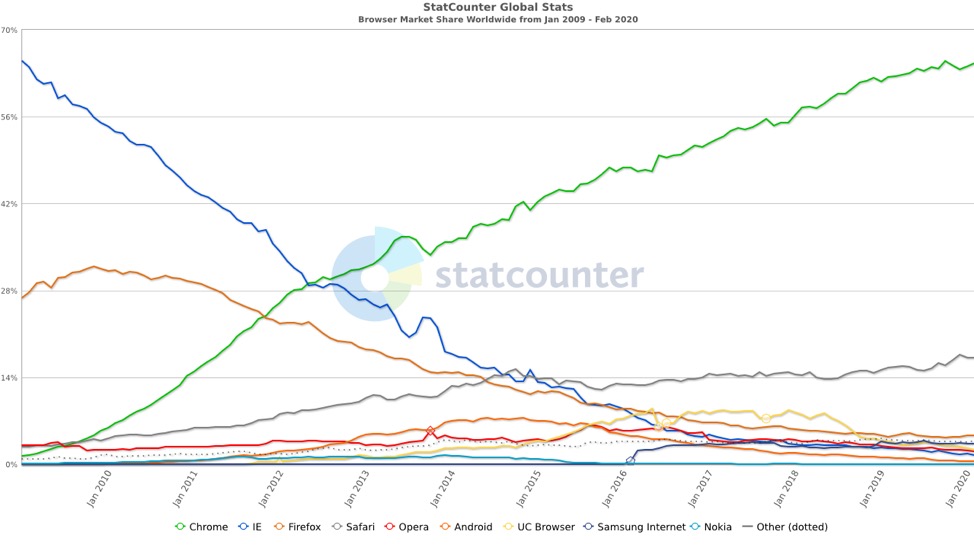

The three most used browsers right now are Chrome, Safari, and Firefox, but more privacy conscious alternatives like Brave are growing fast. Chrome is used the most (64% of the world’s devices), followed by Safari with 18% (and tablets with up to 60%), and Firefox with around 4% (less than 1% on mobile), according to this summary. What this power block does with their technologies, guiding 76% – 85% of the world’s traffic, is key in understanding what you should use for your online marketing.

Mozilla Firefox

Mozilla has around 4% of the overall market share, with an estimated range between 8% and 12% on desktop and <1% on mobile (sources Statcounter, NetmarketShare and WikiMedia). It offers privacy protection against fingerprinting and third-party cookies using Enhanced Tracking Protection (ETP).

ETP blocks all third-party cookies if they are on this list from Disconnect. First-party cookies are not blocked and the Disconnect list seems to be categorized using an intermediate step and maybe replaced altogether with a Mozilla curated list, according to their community conversations. Maintaining this list is a fairly labor-intensive process, but a solid step toward privacy. Once a source is on the list, no third-party cookies from that can be set. There is no clear roadmap of where Mozilla Firefox ETP is heading, but the priority seems to be the refinement, categorization and expansion of the cookies list and fingerprinting.

Apple Safari

The default iOS browser has a market share between 20% and 60% on mobile and tablet, according to Wikipedia (November 2019). The overall market share is 18%. Safari is the most vocal browser about privacy. In 2019, it came out with ITP 2.1, ITP 2.2 and ITP 2.3. This is also the team at Webkit behind ITP, pushing on alternative solutions for the problems ITP introduced.

Now let’s take a closer look at LoggedIn, Private Click Measurement and Storage Access API and see how they can solve some of the problems introduced in 2019.

isLoggedIn

John Wilander of Apple Webkit proposed a W3C improvement (in September 2019) on a standard that can assist with the GDPR’s legal basis of a contract. In Europe, that legal base offers the freedom to use cookies on users and a lot more, but only with user consent. Wilander proposes to use something similar at a browser level. This is something I think browsers will accept as a legal base in the future.

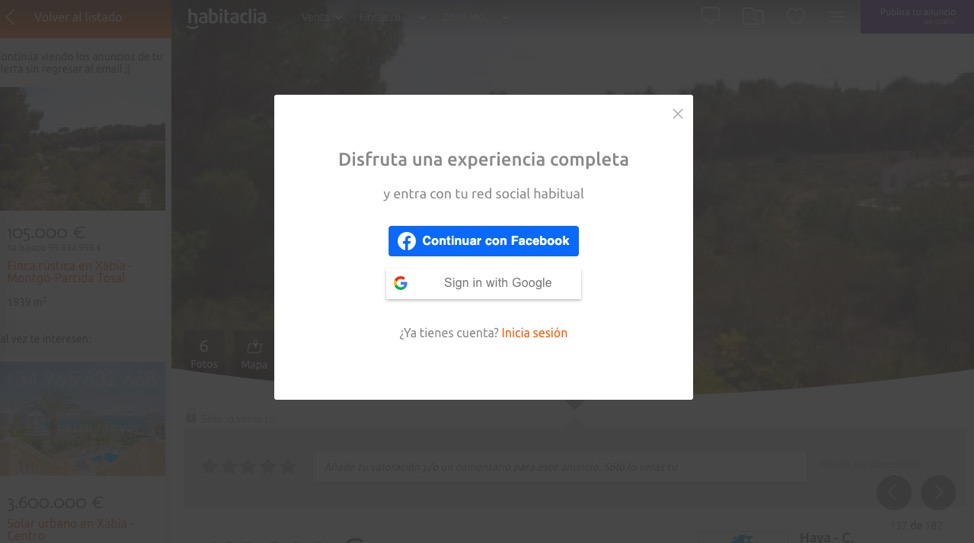

isLoggedIn is a browser feature which could deny client-side state (e.g. non-session cookies, localStorage) unless the user is logged into a trustworthy provider. There is fear that the obsession to get user data can lead to pointless logins just to get to the isLoggedIn state and the GDPR legal base ‘contract’ to do things like ad retargeting. I’ve experienced this firsthand. In the example below, the Spanish real estate site Habitaclia is trying to have me log in, while the information is available by closing the pop-up. The value of logging in for me as a user is null, so this practice is seemingly pointless (mind you, this is from Spain, where the GDPR is enforced).

But like ITP, isLoggedIn will be tried and improved, and I hope it gets adapted. There was a lot of back and forth on it in 2019 in the W3C channel, but no further actions were made since then. In theory, this could create a technical solution for the legal base stickiness that now only cookies and consent can provide. In Europe, this would offer a simple way for all tools to know if a user is logged in on a site and if there is a legal base to collect personal data.

Private Click Measurement

The Private Click Measurement (previously called Privacy-Preserving Ad Click Attribution), by the Webkit team, is a W3C proposal that would allow simple but effective attribution of conversions. It’s a more formal proposal for the improvement of isLoggedIn but not yet considered as a W3C standard. For A/B testing, this may come in handy when converting in a shopping cart environment off-site. It’s something we will consider implementing when it’s available publicly. You can read the implementation suggestion in this article. Mid-January Apple Safari and Mozilla Firefox got behind this initiative to raise it to a formal standard. Its limit is 64 campaigns and a random conversion trigger with a 24-48 hour delay (making it harder for you to pinpoint the conversion, thereby increasing privacy), but with support from Firefox and Safari is seems to get traction.

The llimits are also something the Chrome (Chromium) team finds too restrictive, and it’s the reason they proposed the new Conversion Measurement API.

Google Chrome

Chrome holds over 64% of the market share worldwide (with 67% on desktops alone). Chrome is a powerhouse in the world of browsers and a controversial player where the main revenue comes from Google’s advertising products. With a 25% to 65% share for mobile and 67% for desktop, it’s the world’s most dominant browser. But things change, and we’ve seen it before… browsers can fall out of favor. All the Android pre-installations might not save Google Chrome if they do not shift their focus to privacy.

Digiday summarizes this nicely:

Recent changes to restrict third-party tracking in Apple’s Safari and Mozilla’s Firefox browsers have proven to be disruptive for publishers, ad tech vendors, and agencies. Still, with web privacy increasingly becoming a mainstream consumer concern, Google is under some competitive pressure to directionally follow suit.

Ian Lowe, VP marketing at the consent management platform Crownpeak states:

As pressure mounts, Google is looking to show more and more ways of moving positively in the privacy direction while still maintaining the revenue model.

SameSite

The SameSite update of February 2020 regarding Chrome 80 will require website owners to explicitly label the third-party cookies that can be used on other sites. Digiday explains the change really well:

Google first announced in May last year that cookies that do not include the “SameSite=None” and “Secure” labels won’t be accessible by third parties, such as ad tech companies, in Chrome version 80 and beyond. The Secure label means cookies need to be set and read via HTTPS connections.

Right now, the Chrome SameSite cookie default is: “None,” which allows third-party cookies to track users across sites. But from February, cookies will default into “SameSite=Lax,” which means cookies are only set when the domain in the URL of the browser matches the domain of the cookie — a first-party cookie.

Any cookie with the “SameSite=None” label must also have a secure flag, meaning it will only be created and sent through requests made over HTTPs. Meanwhile, the “SameSite=Strict” designation restricts cross-site sharing altogether, even between different domains that are owned by the same publisher.”

Mozilla’s Firefox and Microsoft’s Edge announced they will also adopt the SameSite=Lax default. Without this labeling, we will start seeing more and more warnings in the Chrome console pop-up like the one below.

According to Digiday :

Google’s February SameSite and Google Ads update will prevent ad tech companies who don’t have a primary relationship with a consumer from “listening in” to ad auctions in order to build user profiles using content categories. Under the current system, if a user visits a site like ESPN.com, Google’s exchange sends back information in the bid-stream that includes the contextual subject “sports” to potential bidders. A demand-side platform and other ad tech companies like data-management platforms are able to see that information and could, theoretically, use it to create behavioral user-profiles unbeknownst to the user. It’s not clear if this happens regularly in practice, but the possibility presents a GDPR risk. Building profiles of users based on bid data is also prohibited by Google’s ad policies.

SameSite changes seem to fall under a more general project Google Chrome is working on called the Privacy Sandbox.

Privacy Sandbox

The Privacy Sandbox’s mission is to “create a thriving web ecosystem that is respectful of users and private by default”, according to this Chromium page. Chrome’s general approach, just like Webkit’s, is to re-enable cross-site tracking but without privacy implications for the users. This means they don’t want to lose the ad capabilities, but can also see that privacy becomes an issue they can no longer ignore.

Here’s a telling statement from the team:

We believe that part of the magic of the web is that content creators can publish without any gatekeepers and that the web’s users can access that information freely because the content creators can fund themselves through online advertising. That advertising is vastly more valuable to publishers and advertisers and more engaging and less annoying to users when it is relevant to the user. We plan to introduce new functionality to serve the use cases that are part of a healthy web that is currently accomplished through cross-site tracking (or methods that are indistinguishable from cross-site tracking). As that functionality becomes available we will place more and more restrictions on the use of third-party cookies, which are the most common mechanism for cross-site tracking today and eventually deprecate them entirely. In parallel to that, we will aggressively combat the current techniques for non-cookie based cross-site tracking, such as fingerprinting, cache inspection, link decoration, network tracking and Personally-Identifying Information (PII) joins.

Michael Kleber, a Google software engineer who works on privacy and tracking prevention in Chrome, outlines the company’s plan to move towards a web without tracking. He suggests shifting from cookies to “more right-sized APIs” that don’t allow for unfettered tracking of individuals across the web and discusses how Chrome is exploring the use of Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC) (part of the Privacy Sandbox project) to continue to allow interest-based ads on the web. He encourages developers to “help us imagine a world without third-party cookies or other tracking vectors.”

Declaring First-Party Cookies Belonging to the Same Organization

Another project Chrome is working on under the Privacy Sandbox initiative is First Party Sets (Justin Schuh, Director of Chrome Engineering started talking about this in August 2019).

This project proposes a new web platform mechanism to declare a collection of related domains as a First-Party Set. It’s an iteration of Wilander’s “Single Trust and Same-Origin Policy v2” and “affiliated domains”.

Here, the browser will consider domains to be members of a set if the domains opt in and the set meets the UA policy, to incorporate both user and site needs. Domains opt in by hosting a JSON manifest at https://<domain>/.well-known/first-party-set. The secondary domains point to the owning domain while the owning domain lists the members of the set, a version number to trigger updates, and a set of signed assertions to inform UA policy. Here’s an example of this:

https://a.example/.well-known/first-party-set

{ "owner": "a.example",

"version": 1,

"members": ["b.example", "c.example"],

"assertions": {

"chrome-fps-v1" : "<base64 contents...>",

"firefox-fps-v1" : "<base64 contents...>",

"safari-fps-v1": "<base64 contents...>"

},

}

https://b.example/.well-known/first-party-set

{ "owner": "a.example" }

https://c.example/.well-known/first-party-set

{ "owner": "a.example" }Declaring your first-party domains to the browsers allows you to include all domains of your organization. This is making it easier for browsers to block third-party tools that lift on first-party cookies and scripts. If you have personalization, A/B testing, analytics, attribution systems or referral tools, bring them under your organization’s domains, like server-side cookies and CNAME. Be sure to check which parties you bring under your domains as they become your responsibility (soon you’ll have to declare them to the browser ‘customs’ before entering the visitor device).

Conversion Measurement API

Referring to Conversion Measurement API specs, Steven Englehardt from Mozilla said:

I would like to voice Mozilla’s concerns regarding the introduction of a high-entropy cross-site identifier, which I also expressed at the aforementioned TPAC meeting. The high-entropy “impression data” identifier gives the publisher site the ability to learn information about an individual user’s activity on a site other than their own. This is an explicit violation of Firefox’s anti-tracking policy, and we are not going to implement an API that facilitates such a violation because it enables cross-site tracking. The publisher site can learn information about individuals by associating the “impression data” value with a user identifier at the time of conversion registration (i.e., when the user clicks on an ad on the publisher site). Then, information revealed by the “conversion-metadata” value can be associated with that user’s account through the link created by the “impression data” value. In practice, this may be sensitive information like whether that user made a purchase on the destination site, or whether they registered for an account. To understand the severity of the risk associated with allowing the publisher to collect activity data associated with an individual through this API, consider that the publisher may be a search engine or social network that acts as a user’s primary access point to the rest of the web. Publishers in this position are likely to learn about an individual user’s activity on a large number of destination sites, and thus build a fairly comprehensive picture of that user’s off-site purchase activity, off-site registration activity, and so on.

Also, Safari (Webkit) states public skepticism, especially around the 64-bit impression metadata.

One way or another, all the other browsers are looking to solve the attribution problem for advertisers by using either the Conversion Measurement API proposed by Chrome or the Private Click Measurement API proposed by Safari. Once this is in place, all browsers will offer advertisers enough incentives to work with them while still protecting web privacy.

Turtledove or Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC)

Michael Kleber developed a new proposal called Two Uncorrelated Requests, Then Locally-Executed Decision On Victory (TURTLE-DOV) or TURTLEDOVE (updated version of PIGIN).

Although it’s not yet clear how Turtledove or the Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC) will turn out, the team at Chrome is putting all these solutions up for discussion and see which gets traction from the privacy teams of Safari, Firefox, and Brave. The FLoC proposal offers a different approach to ad targeting, focusing on people’s general interests rather than on specific actions.

In the FLoC model, advertisers and ad networks have no control over what groups people are in. Instead, the browser itself is responsible for somehow grouping together flocks of “similar people”, with wide latitude in how it comes up with its notion of similarity. The browser can then take steps to prevent its grouping from allowing tracking or revealing sensitive characteristics. PIGIN meets this use case, and some of that explainer is reused here. In that proposal, the browser was in control of interest group membership (as in this one), but a small amount of interest group information was sent along with the regular contextual ad request (and there was no in-browser auction).

11: fake out, ending remix

— pes (@pes10k) February 8, 2020

Needed extra detail: Brave gets the ads to locally match with you periodically, on a schedule way unrelated to your browsing. Everyone holds the catalogue (ads are small on Brave)!

Feedback from the W3C Web-Advertising Business Group and Privacy Interest Group and from the browser and privacy research communities highlighted weaknesses in this design.

The ability to associate an advertiser’s interest group assignment with a person’s first-party identity on a publisher’s site is considered too high of a privacy leak even with that Explainer’s proposed mitigations. Analysis of real-world user list memberships shows that even the proposed “small amount of interest group information” would consume too much of a page’s Privacy Budget. The addition of an in-browser auction in TURTLEDOVE is a way to address both privacy weaknesses. Discussions with participants in the ads ecosystem have made it seem more plausible that an in-browser auction component could be adopted.

How would TURTLEDOVE work? The proposal is a new API to address this use case while offering some key privacy advances:

- The browser, not the advertiser, holds the information about what the advertiser thinks interests a person.

- Advertisers can serve ads based on interest, but cannot combine that interest with other information about the person — in particular, who they are or what pages they are visiting.

- The websites the person visits, and the ad networks those sites use, cannot learn about their visitors’ ad interests.

This seems like a good solution for privacy, and it makes the browser a powerful player in the advertising world. That way, I see companies like Apple (Safari Webkit), Firefox and Brave stand behind this as new models of revenue, while still respecting privacy. Still, this would require a massive power shift from ad networks to browsers.

Server Side Will Save Us All

Some vendors pretend that the server side method solves all problems and that it allows personalization or A/B testing. But the server-side method won’t allow you to do much without understanding the state of the client (user in a browser). For that, you still need first-party cookies. How do you set these first-party cookies? You need to present the same variations for A/B tests and personalization in a way it sticks across sessions for this to work. Fingerprinting is not legal and browsers are tracking and disabling these methods. It’s not transparent at all. You can only use first-party cookies set under a subdomain of the main site and use First Party Sets to state you own this subdomain.

Client-side vs server-side is not a debate that makes sense in this discussion.

You might call client site personalization and A/B testing tools hybrids, as they move the cookie-setting responsibility to a trusted domain (First Party Sets) within the organization. However, in that case all client site tools would be hybrids, as this will be the only way to do this in the future.

Removal of Third-Party Cookies. What’s Next?

The signs are clear, cookies are dead… well, not really. Most articles online talk about the death of cookies. Although we’ve seen a lot of APIs that can take over part of the cookies’ job, there is no sign that cookies are going anywhere yet.

Third-party cookies will disappear completely, and that is a good thing for privacy.

Justin Schuh, Director at Chrome Engineering recently stated: “We plan to phase out support for third-party cookies in Chrome (and) our intention is to do this within two years”. Chrome will start with the conversion marketers as they plan to start the first origin trials by the end of 2020, starting with conversion measurement and following with personalization.

Webkit (Apple Safari) and Chrome (Google) will help lead the way for browser privacy, Apple pushing Google to go for more privacy while not addressing many of the iOS money maker privacy issues.

I’m predicting more and more European businesses will focus on trying to get users to log in and register (hopefully not using Google or Apple services) and apply the legal base on contract.

The interest in optimizing consent or presenting some benefit at the login phase (like Amazon’s one-click) makes it clear that the battle in Europe will be all about logins.

As optimizers, we will need to make sure that on an organizational level we have all (first-party) domains ready to share with browsers. A step in that direction can be making an inventory of the scripts and providers that are privacy-friendly. Then, giving that first-party cookie access over your central CNAME solution while keeping any privacy-sensitive tools (building cross-site profiles).

We will be legally required to ask for consent in the UK (according to the ICO), but I foresee that CNIL’s guidelines for exceptions on A/B testing and limited analytics will pave the way for a European exception for those since that would match the new ePrivacy Regulations. Without it, we’ll only have session-based analytics, and won’t be able to connect to individual users. A/B testing using the standard user-level monitor and conversion loop does not apply in this case and we’ll have to fall back on continuous improvement, monitoring these conversion improvements and correlating them.

Non-Europeans can be tested on using first-party cookies (the ones Convert Experiences provides) and should begin with an inventory of all the scripts and vendors the organization trusts to bring these to subdomains using CNAMEs. The conversions can be tracked using the different Click or Conversion Attribution APIs that are being developed. Perhaps A/B testing can lift on these for the different variations and keep consistency if browsers don’t follow CNIL’s thinking in excluding these from cookie blocks, although in the current formats that seems unlikely. Consistency comes from the first-party trusted cookies.

User-based analytics using techniques like isLoggedIn will likely be extended and unified across browsers, allowing privacy laws to shift the responsibility of defining the contract to browser mechanisms. This gives browsers a new power. Combined with new APIs for intent measurements, ad categories and conversion tracking, the battle is on for who owns the biggest browser market share, and offers the biggest ad networks in the world.

Interesting times ahead… I really hope this article helps you get clarity on where privacy laws and browsers are likely to go. One thing’s for certain. Prepare your optimization and analytics team to plan for making the changes when the time comes (it will be sooner than you think).

Have any questions? Let’s continue the conversation on LinkedIn.

Written By

Dennis van der Heijden

Edited By

Carmen Apostu