From Stoicism to Betting, Ryan Lucht of CRO Metrics and Positive John Talk About Why Experimentation Is Life

Experimentation isn’t just a method. It is a way of life.

This becomes super clear after listening to the deep dive between Ryan Lucht, Director of Growth Strategy at Cro Metrics and Positive John, Product Growth and Experimentation Consultant at Positive Experiments.

In this illuminating chat, they go deep into the essence of experimentation, drawing from the diverse wellsprings of their combined professional experiences and the rich philosophical troves of stoicism.

Together, they weave a compelling narrative that places experimentation at the heart of learning, growth, and success in life.

Discover how they apply these in handling business uncertainties, why they see experimentation as a way of life, and their shared belief that a true experimenter’s journey is marked not just by the destination but also by the enriching process of getting there

Let’s savor this refreshing mix of philosophy, experimentation, business, and life.

What’s the Color of Your Thoughts? Mental Models For Experimentation Practitioners

In the fascinating realm of experimentation, mental models play a critical role.

They shape how we approach, understand, and navigate through challenges. And a great mental model that has a profound influence on CROs is stoicism.

When experimenters stick to this ancient philosophy, they usually champion an attitude of open-mindedness, resilience in the face of setbacks, and an unwavering commitment to ethical practices and continuous learning.

We have stoics over here at Convert. And we adore them. Our CEO Dennis van der Heijden has applied stoic minimalistic approaches to his life and has been writing about it on LinkedIn for close to a decade now:

But the joy doesn’t end there… Many of our very favorite practitioners including PJ Ostrowski and Ryan Lucht swim in the deep waters of stoic wisdom.

This interview kicked off with PJ asking Ryan about the color of his thoughts:

The soul is dyed the color of its thoughts.

Heraclitus

Ryan says we often let our minds and thoughts run on autopilot, but this leaves us as mere passengers.

If we’re intentional about our thoughts and the contents of our minds, we can create a solid foundation for the environment we want to exist in.

A loving atmosphere in your home is the foundation for your life.

The Dalai Lama.

We’re just getting started…

More Stoic Mental Models We Apply to Experimentation

There are more stoic mental models that are instrumental in developing the “attitude of open-mindedness, resilience in the face of setbacks, and an unwavering commitment to ethical practices and continuous learning.”

They are:

1. Embracing Uncertainty

The more we value things outside our control, the less control we have.

Marcus Aurelius

Stoicism teaches us to focus on what we can control and to let go of what we can’t. It emphasizes the cultivation of virtues like wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance.

In experimentation, the outcome of a test is largely outside our control. We do not know—in most cases—the verdict people will hand in for the change you’ve made, the product you’ve launched, and the UI you have presented.

An obsessive focus on conversion rate thus leads to perverse incentives and what Haley Carpenter would refer to as a lack of experimentation rigor.

We appreciate the approach Speero takes since their metric charts and blueprints are more about input and output metrics (which are to do with the quality of insights, speed of execution, and due diligence) than outcome metrics.

The result is more productive testing practices and a healthier mindset, since we focus on the aspects we can control and improve, rather than fretting over the aspects we can’t.

2. Grounding Yourself in the Present

Confine yourself to the present.

Marcus Aurelius

Living in the present is an especially valuable mindset for an experimenter. Two ways you can achieve this:

First, remain vigilant and responsive to the here and now. Monitoring the process and reviewing results to detect validity threats like SRM saves your test from unforeseen interferences.

Second, living in the present means not obsessing over future outcomes. This means no peeking in to see whether your test is showing signs of being the winner.

Trust in the (scientific) process and live in the present. Take the lag between execution and result as a sort of incubation period — a valuable window where the foundation of tangible insights is laid.

3. Optimizing Your Efforts

Make the best use of what is in your power, and take the rest as it happens.

Epictetus

Last but not least… The worst oversight in an experiment is running an underpowered test. And then rejoicing in the results.

An underpowered test could lead to inconclusive results or worse, misleading conclusions. So, how do you avoid this common testing mistake?

Make sure you take pre-test analysis seriously, know your sample size, and let the experiment run its course!

The Whys of an Experimenter

What do you do, how do you do it, and why do you do it?

Positive John

People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.

Simon Sinek

In this context, Ryan talked about Simon Sinek’s ‘levels of why,’ and how that relates to his experience as an experimentation practitioner.

His top-level ‘why’ is that businesses who experiment win. They allocate resources better, find unexpected opportunities, and in general, just run the business smarter by avoiding a lot of mistakes.

But the real magic goes beyond just winning experiments.

His deeper level ‘why’ links to how experimentation changes the way we think and act — a culture change. If experiments guide your decision-making, you’ll soon embody equanimity. It’s like the Buddhist sublime attitude of realizing that reality is transient; nothing lasts forever.

Clinging tightly to our ideas or desired results is not going to help. Instead, we should follow where the discoveries lead us. Learn to be wrong and accept that reality.

This makes you more adept at playing your Humble Card. It teaches us not to see ourselves or others as know-it-alls. Because, let’s face it, nobody knows everything. Experimentation reminds us of that, and it’s kind of cool, don’t you think?

Speaking of the “humble card”…

The Journey to Acquiring the “Humble Card”

How was the journey getting to the point in your career where it clicked for you that you don’t always hold the best ideas?

Positive John

Three instances paved the way to the “humble card” for Ryan:

First off, he noticed something interesting while working with more than 10 strategists at Cro Metrics.

Although this pool of qualified strategists who mainly were responsible for test roadmaps and hypotheses with varying levels of experience and completely different perspectives, no single strategist or client was more than 1 standard deviation away from the mean when it came to the win rate.

If you’ve already observed this in your journey as an experimenter, you probably asked yourself the same question Ryan did:

I am not an idiot, I’ve run several thousands of tests on this stuff, why am I not better at predicting?

Ryan Lucht

Ryan answered his own question, “If we were good at predicting, we wouldn’t need experimentation.”

Then he read the book, “Fooled by Randomness” by Nassim Taleb. The book also sheds light on the influence of chance or happenstance on how events unfold in our lives… or indeed which tests win.

Ryan realized that even though good research and insights can influence how a program turns out, this element of ‘randomness’ always lurks in the background. It’s like a reminder that we humans are not always the best at judging the quality of ideas. That’s why we should question everything (stoics totally agree with that, by the way), and, you guessed it, test everything!

Sometimes we think we know which experiment will win, but the actual results can still surprise us. We might find that the ‘win’ we were expecting stands for something completely different — like some insights or trade-offs that eluded us.

Taking Better Decisions Or Avoiding Mistakes? What Stance to Take With Senior Leadership When Positioning Experimentation?

Where’s the balance between taking better decisions and avoiding mistakes?

Positive John

An impactful book in this area for Ryan is “How to Decide” by Annie Duke. It teaches that correlating the outcome of our decisions with the quality of the decision-making process is a mistake. Annie calls this “resulting”.

You can make a great decision and get unlucky or make a bad decision and get lucky. A strategic approach to decision-making starts with separating the outcome from the quality of your decisions.

The outcome is the by-product of insights and execution, but also randomness (or chance). We can’t control chance! So to simplify the “good outcomes” equation, it is essential to focus on elevating how great decisions are taken. Focus on the input, rather than the outcome.

Ben Labay has also spoken about “resulting” and how it connects to confirmation bias in experimentation recently:

How much of this decision-making process that you’ve applied in business can you also apply to your personal life?

Positive John

The framework of good decision-making benefits both personal and professional decisions.

Let’s take an example. If you’re making changes to a website, you try out different things and see what works best. This gives you ‘causal inference’, which is just a fancy way of saying you get a clear idea of what causes what.

But life decisions? It is a bit more difficult to test life decisions like changing states for example, since we simultaneously can not do and not do it.

And PJ made an incredible contribution to that:

Get comfortable with frequent, small failures. If you’re willing to bleed a little bit every day, but in exchange, you win big later, you’ll be better off.

Naval Ravikant

Here’s the deal: when you make good decisions, any mistakes or failures you experience usually aren’t that big. They’re small bumps in the road that you can easily get over. But if you make a really bad decision? That can lead to a massive failure, one that might take away from your ability to bounce back and have a big win.

This is why good decision-making is so important. It’s like your secret weapon against big failures.

Think of it like basketball: you want to take as many shots as you can. But, you wouldn’t just wildly throw the ball every chance you got. You’d aim, take a moment to gauge the distance, and maybe even think back on how you’ve thrown in the past.

That’s what ‘due diligence’ means in this context. It’s about using what you know, the data and insights you’ve collected, to make sure every shot you take has the best chance of going in while keeping the potential massive failures at bay.

The Cro Show: Which Test Won?

Everyone likes to play Which Test Won. Here’s Ryan talking about it:

Check out a past episode of the Cro Show.

The Cro Show started as a marketing campaign but morphed into something totally different. A recruitment tool! Absolute curveball. The show is now maintained by HR at Cro Metrics.

This show gets you used to the idea of being surprised. And if you’re truly living the spirit of experimentation, you know by now that’s the constant: surprises.

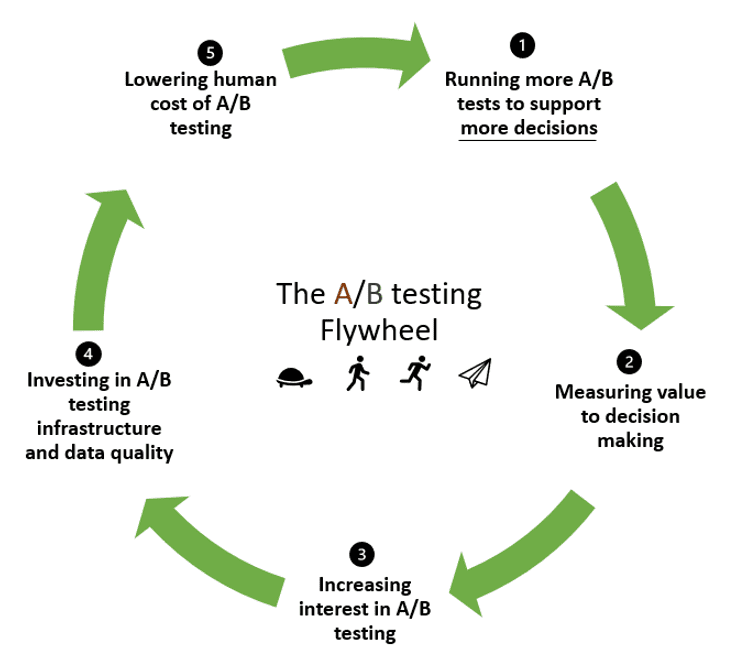

The fact that we are captivated by the idea of betting on outcomes, irrespective of the actual unfoldment of the outcome, is a friend and ally when it comes to speeding up the experimentation flywheel (step 3). The more intrigued people feel the more traction and momentum you build.

There’s a great story from Ronny Kohavi, who used to work at Microsoft. He used to gather a group of people and have them guess the outcome of different tests. They would keep their hands up as long as their guesses were correct. But here’s the thing: by the third guess, everyone’s hands would be humbled.

That goes to show how much we need experimentation. We might think we know what’s going to happen, but the truth is, we’re often surprised.

From Guessing to Prioritize to Betting to Prioritize: Why This Actually Makes Sense

👋🏽 Heads up: Take this discussion in the spirit of fun and thinking outside the box!

In the dynamic world of A/B testing, one intriguing subject keeps popping up: how can we maximize the success rate of our tests?

This isn’t a mere curiosity, it’s a vital concern when we recognize that in software, success rates of A/B tests range from a modest 8% to a more respectable 33%. This statistical puzzle has drawn the attention of some of the sharpest minds in the field.

Ronny Kohavi, a leading voice in the domain of experimentation, recently shared his thoughts on LinkedIn:

And then Jakub Linowski weighed in. He suggested several factors that could potentially influence the success rate of experiments.

I think the question of what drives experiment success rates is interesting and perhaps can equally be treated as a measurable experiment? 🙂

Some variables I’d watch for:

1. Degree of Replication. The more an idea has been tested in different contexts, the more the probability of it working in the future (my bet).

2. Intuition. Our hunches are actually more positive than randomness as we investigated a few months ago: Beyond Opinions About Opinions: What 70,149 Guesses Tell Us About Predicting A/B Tests

3. Crowd bets. If we average our bets, are we then better able to predict outcomes? (I’d bet that yes)

4. Degree of Optimality. If we’re running experiments in highly optimized settings (ex: Bing?) our success rates should drop from regression to the mean. If on the other hand, we’re starting conversion / UI-focused optimization experiments for a new website that has a lot of upside (and we have some common knowledge) then our success rates should be higher.

5. Degree of Exploring vs Exploiting. Similar to the above, if we’re exploiting (or replicating) something we’ve seen work in the past, I’d imagine higher success rates than on more exploratory experiments (which of course are equally important).

Jakub Linowski (via LinkedIn)

Guessing which test won sounds like a simple, fun game. But you can take it up a notch by betting instead.

No, not gambling. The real world of experimentation is a serious matter. Adding stakes to your version of Which Test Won removes that element of just making random guesses. It makes your players choose a side and stick to a decision they believe they’re confident in.

This is even more impactful, making players think “If I was that confident about the wrong answer, what else could I be wrong about?” Cue: The humble card.

Curiously enough, as Simon Girardin found in our last Positive Chat with PJ, prioritization is an area that suffers from a lack of rigor and objectivity. Apparently, the factors we use to create a prioritization framework are often chosen rather arbitrarily, and even their importance, or “weight,” is usually based on guesswork. And as Ryan pointed out, most win rates are really just one standard deviation from the mean, indicating that we humans are not so good at making predictions.

But what happens when we start betting on tests instead of just guessing? When we not only anticipate the outcome but also express our confidence in it (for instance, saying “I’m 35% confident this test will be a winner”)? That’s when things get interesting.

By doing this, we bring to light the ideas where there’s a range of confidence in the bets. This variation shows us that these are the tests we should run first because they present the most significant potential for learning. We’re not just shooting in the dark here; we’re placing our bets wisely and learning as we go. And that, in the end, is the true essence of experimentation.

Prioritization in Experiments and In Life

PJ delves into his unique strategy for prioritizing experiments.

He considers the team’s passion and confidence in their proposed tests. He prioritizes based on how bullish a team is about a particular bet and reach.

Ryan reacted to that strategy. Let’s roll the tape:

According to Ryan, ‘Reach’ could be further broken down into a series of targeted questions with yes/no answers.

For example, instead of merely discussing the general impact of a proposed test, we could ask: “Will this test affect 100,000 visitors?” or “Is the proposed change above the fold?”. These questions add a layer of specificity and objectivity, which can guide the decision-making process in a more strategic direction.

When it comes to betting on tests, Ryan advises that there should be a cap on the amount you can bet on one test. He explains that the greatest cost of running a test in a program where the process is reasonably streamlined isn’t the actual execution, but rather the opportunity cost of not running the next test.

We not only want to make running a test inexpensive in the real world, but also inexpensive to let a test enter the “consideration set” of experiments to be run.

Another concept that Ryan loves is The Institutional Yes from Amazon. Essentially, anyone who wants to run a test is always given a green light by the institution. If someone has an objection to the test, the responsibility falls on them to justify their reservations, not on the person who proposed the idea.

This concept echoes the principles of Holacracy. Each team member is free to operate in whatever way they deem best to energize their role’s purpose unless they are impinging on the territory of another role holder.

The Institutional Yes in Times of Stagflation

In this challenging economic environment characterized by stagnant growth and rising inflation, it’s crucial to adapt and innovate (we’ve done an extensive treatise on how experimentation helps in economic slowdowns).

But is it possible to keep the principle of the ‘Institutional Yes’ alive amid the headwinds of stagflation? And how does that feel?

In essence, the Institutional Yes depends on your unique context. It’s very different at Facebook and Amazon, compared to a smaller experimentation program with dev work that needs to be outsourced.

But even in smaller companies and organizations, it is still possible to implement the Institutional Yes. As long as the prerequisites of the ideas being innovative (substantial) and aligned with the strategic goals of the business are met, don’t hesitate to try again.

Here’s an important reminder:

Treat ideas as fungible. Ideas are commodities. Everyone’s got them. There are lots of them. They’re near infinite. You can always get more.

Ryan Lucht

The key is not to hoard ideas but to be willing to explore them, test them out. Don’t be afraid to run out of ideas because you can always generate more.

Embrace this mindset and you’ll discover how to effectively navigate the ever-evolving business landscape, even in times of stagflation.

What To Do When You Can’t A/B Test?

In this industry, we always push the idea of A/B testing as the gold standard of making decisions. It happens to be the best available tool out there. But when that’s not the case, how would you go about coaching people on trying the second best option?

Positive John

Ryan’s right. The “A/B test everything” maxim comes from us trying to emulate FAANG companies and their approach to experimentation. Their ability to conduct extensive testing due to their large user bases and ample resources is something many smaller companies aspire to replicate.

But what happens when A/B testing isn’t an option?

When you move down the hierarchy of evidence, where A/B testing isn’t viable due to resource constraints or lack of sufficient traffic, it’s essential to diversify your approach.

Instead of relying on one piece of evidence or data source, seek out multiple viewpoints, from expert opinions to industry trends or customer feedback. This strategy, known as the triangulation of data, allows you to find points of convergence among these different sources and derive a more comprehensive and credible understanding of your situation.

Hedge your bets. Aim to make the best decision possible given the information and resources at your disposal. You may not always have the perfect data set or the ideal circumstances for an A/B test, but that doesn’t mean you can’t make informed decisions.

Use every tool in your arsenal, from intuition and industry knowledge to customer insights and analytics, to make the best choice possible under the circumstances.

In essence, when A/B testing isn’t feasible, you don’t throw your hands up and surrender to guesswork. You adapt, diversify, and make the best use of what’s available to you. For example, when you absolutely have to do a website redesign in the absence of reliable data and insights.

Website Redesign: “Hedging” in Testing?

The key point highlighted is the notion of ‘hedging’ in testing, specifically in the context of a website redesign. In other words, instead of expecting a massive uplift from a redesign, we focus our attention on avoiding disastrous outcomes.

The premise here is simple: a website redesign is a considerable undertaking, and the last thing we want is for it to result in a substantial downturn in user engagement or conversions.

Here’s another crucial way you should think…

Ranges of Outcomes: A Mental Model For Non-Testers

People don’t really think in ranges of outcomes nearly as much as they should. Any decision we make has a range of outcomes. It’s usually luck that determines the upper bound and lower bound.

Ryan Lucht

In response to “What is your experience getting non-statisticians to move from thinking in terms of point estimates to a range of outcomes?”, Ryan said:

These outcomes—upper and lower bound stretching from the most unfavorable to the most advantageous—are largely determined by the unpredictable factor we often refer to as chance or luck.

It’s our job to do our best to understand the breadth (range of different outcomes) and intensity (the impact of each outcome) that could result from our choices.

To help with this, statisticians use concepts like credible intervals and confidence intervals. While these may sound complicated, they essentially provide a range within which we expect a particular outcome to fall, given the data we have.

Confidence intervals are associated with Frequentist statistics, while credible intervals are associated with Bayesian statistics, which is an alternative interpretation of statistical evidence.

In Bayesian thinking, all probabilities are subjective. They represent our current belief or estimation about the likelihood of an event happening, based on the information we have at hand. And these probabilities can change as we gather more information or evidence.

Both Frequentist and Bayesian statistical approaches don’t really focus on the accuracy of the actual result. Instead, they provide us with measures like statistical significance or probability to be best, which help us understand how confident we can be about our conclusions based on the data.

However, none of these measures can provide a guarantee of the actual magnitude of the uplift or the improvement we’ll see.

This is where we need to shift our mindset from expecting binary, black-or-white results, to understanding that there is a spectrum of possibilities or a window of outcomes.

This way, we are better equipped to deal with the inherent uncertainties and complexities that come with decision-making, both in testing and in life.

But what is the root of this point estimate type of thinking in the first place?

Why do we think in terms of accuracy and absolutes, and not ranges?

Positive John

Does a Career in Experimentation Make a Good Founder?

As Ryan states, there are transferrable experimentation skills that can pave the way to becoming a successful CMO, and by extension CEO and founder.

Also, much of the ethos that drives the field of experimentation aligns closely with the principles of the lean startup methodology, which is often employed by successful entrepreneurs. Both rely on the idea of trying something, learning from it, and then iterating based on the results.

A career in experimentation doesn’t just equip you with technical skills; it also cultivates a mindset of iterative learning and data-informed decision-making.

This combination makes it an excellent foundation for those aspiring to be founders, as it prepares them to lead in an environment where informed decision-making, risk management, and constant adaptation are key to success.

Quotes and Takeaways

- If we’re intentional about our thoughts and the contents of our minds, we can create a solid foundation for the environment we want to exist in.

- Stoic experimenters have an attitude of open-mindedness, resilience in the face of setbacks, and an unwavering commitment to ethical practices and continuous learning.

- “If we were good at predicting, we wouldn’t need experimentation.” — Ryan

- “Treat ideas as fungible.” — Ryan

- “Any decision we make has a range of outcomes. It’s usually luck that determines the upper bound and lower bound.” — Ryan

Written By

Uwemedimo Usa, Ryan Lucht, John Ostrowski

Edited By

Carmen Apostu