How to Detect and Tackle Perverse Incentives in A/B Testing: Prioritizing Rigor and Process

Have you heard the story of the sea captains who killed their passengers?

In the 1700s, the British government paid captains to transport prisoners to Australia. To cut costs, the captains provided inadequate food and care, so only a few passengers arrived in Australia alive.

The survival rate rose dramatically once the government shifted the incentive, paying captains only for convicts who safely walked off the ship into Australia.

Incentives matter. And just as they once determined life and death at sea, perverse incentives can poison even the noblest of pursuits.

The Embassy of Good Science discusses scientists who, when pressured to publish attention-grabbing results for grants and promotions, may exaggerate findings or omit contradictory data. This is where the term “perverse incentives” has its roots.

In conversion rate optimization, we can observe this when optimizers are gunning for ‘wins’ at all costs, often disregarding rigor, process, and the deeper insights experimentation should provide.

There are two types of perverse incentives:

- Institutional perverse incentives: Results from years of bad practice leading to a poor culture that’s unconducive to a learning-driven scientific process and cares only about the flashy outcomes.

- Inadvertent perverse incentives: Incentives unintentionally woven into the test design that may influence audience behavior and skew results.

Both types demand our attention. The problem lies in how success is often measured.

Whenever we choose a metric, we also need to have a clear objective of what the metric is trying to accomplish. We cannot forget that given a target, people will find the easiest way to get to it. Choosing metrics that are difficult to trick will help [us] get the right outcomes from our investments. We also need to have the policy that for every project that is intended to influence some metrics, we should review if the project’s impact is still aligned with the goal of the product.

Juan M. Lavista Ferres, CVP and Chief Data Scientist at Microsoft in ‘Metrics and the Cobra Effect’

Easily manipulated metrics create fertile ground for perverse incentives to flourish.

This fact, coupled with the looming and obvious presence of monetary considerations, makes Conversion Rate Optimization the ideal stage for perverse incentives to invade.

That is why we say…

You Can’t Eliminate Perverse Incentives From “CRO”

Reason number one is in the name—Conversion Rate Optimization. By design, the focus is on improving conversion rate; a metric that can quickly be taken as a proxy for the health and success of a business. Which is too much of an incomplete picture to judge the health of a business.

Despite this, some consider conversion—micro or macro—proof that they can effectively nudge web traffic to behave in a certain (desirable) way.

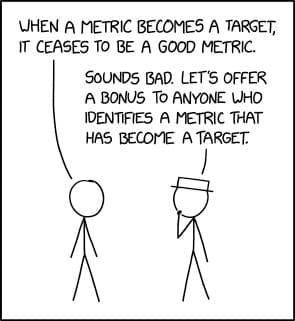

But according to Goodhart’s Law, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure’’ (Mattson et al., 2021).

An example is when surgeons are judged solely based on patient survival rates. They might avoid high-risk but necessary operations, leading to worse overall health outcomes.

And this is what happens if testers obsess—often myopically—over conversion rates.

Craig Sullivan shares an example of how trying to increase conversion rates without context is perverse in and of itself. This is made worse by granular goal selection, shoddy processes, and reporting misdemeanors, which are the classic symptoms of induced perverse incentives in business experiments.

Jonny Longden adds: No one can guarantee improved conversion rates unless they are the CEO!

This, too, is in jest. No one can guarantee more registrations, transactions, or revenue.

The second half of the perverse incentives puzzle involves money—funding, buy-in, salaries, fees, performance-based commissions.

That presents two issues. First, conversion rate optimization focuses on a downstream metric that a single person can’t predictably influence. Second, the folks who claim to improve conversions are often paid based on how well they do so.

A/B testers are incentivized to show results and show them quickly. If 80% of the tests they run come back inconclusive or the test version performs worse than the default—which are typical scenarios—the people budgeting for the testing program might not want to continue it. Similarly, if the testing team tells their bosses that the test will take eight months, and then it needs to be replicated for another six months before determining the validity of the hypothesis, their bosses might scrap the program completely.

Stephen Watts, Sr. SEO and Web Growth Manager at Splunk

Businesses are driven by revenue, and there’s nothing wrong with that. More conversions often translate into more revenue.

But this has created an environment where CRO providers who charge a percentage of the money made through their optimization efforts flourish. They come off as more confident, less of a cost center, and easier to onboard (because they’re an easier sell to skeptical CFOs). A much safer ‘bet’ for the business.

This perpetuates a dangerous cycle. CRO becomes inextricably linked to a single outcome despite its actual value in the breadth of insights it can provide. And that’s just how things are right now.

The Psychology Behind Perverse Incentives

People’s tendency to choose an easier path toward a target can be understood through the lens of self-enhancement, which refers to individuals’ motivations to view themselves positively and validate their self-concept.

Research suggests that individuals may prioritize more accessible options for self-enhancement. However, what is interesting about this in an organizational context is that people are very sensitive to group expectations of self-enhancement (Dufner et. al., 2019).

This explains why different companies or even teams within them can have very different approaches to self-enhancement and, therefore, incentives!

Interestingly, the pursuit of self-enhancement has been associated with short-term benefits but long-term costs. Those who engage more in self-enhancement activity may initially make positive impressions but may experience decreasing levels of self-esteem (Robins and Beer, 2021)—just like the pursuit of test ‘wins’ can harm your long-term strategy. It feels good now, but not so much later. Perverse incentives!

So, perverse incentives in conversion rate optimization programs aren’t a question of “If.” The real questions are: How and to What Extent?

How Perverse Incentives Are Introduced in Your Program

Surveys conducted between 1987 and 2008 revealed that 1 in 50 scientists admitted to either fabricating, falsifying, and/or modifying data in their research at least once.

Sadly, this sobering reality isn’t confined to laboratories and peer-reviewed journals. No one, not even well-intentioned CRO practitioners, is above succumbing to the siren call of perverse incentives.

Here’s how they can creep into your experimentation program:

Testing to Win

Perverse incentives take root where success is always defined as a ‘winning test.’

We’ve already spoken at length about this phenomenon. Teams that view A/B testing in CRO programs as customer research or a chance to learn what matters to audiences are far more likely to develop innovative ideas that solve real problems.

They lay the foundation for strategic, iterative testing where cumulative efforts far outweigh one-off haphazard guesses that can’t build momentum to that elusive big win.

Success in experimentation follows the rule of critical mass, i.e., you must hit a threshold of input (perseverance) before expecting any degree of change (commensurate output).

A/B testers who test to earn units of information from the result, whether win, loss, or inconclusive, tend to exhaust all the possibilities around an insight (hypothesis) before moving on to the next shiny object.

Conversely, testing just to win defeats the whole point of experimentation—which is gathering evidence to establish causality and gauge the potential superiority of interventions. It sacrifices long-term transformation for short-lived gains, leaving companies shy of real transformation. And it plays out in many different ways:

1. Focusing on short-term gains

When you test to win, you naturally gravitate towards ideas and concepts that are easier to impact.

For example, you might want to test introducing a higher discount.

It is tenable that the treatment will win and cart abandonment will be reduced. Depending on your margin, you may be giving away profit that you just can’t afford to. The test won, but your overarching goal—to help the business deepen its pockets—wasn’t achieved! Plus, you learned nothing; discounts are proven to move the needle.

2. Cherry-picking data and fudging reports

The looming specter of failure tests an optimizer’s integrity. It goes something like this:

- Winning is the only acceptable outcome. If you don’t keep up a steady supply of wins (i.e., improved conversions because the metric is the king), then your contribution to the business will be questioned.

- 9 out of 10 ideas fail to change user behavior significantly. So you will see a lot of red across the board.

- When the defining KPI suffers, you find succor in the arms of hypersegmentation. Overall, the test did lose, but it outperformed the control for users on an iPad.

- Does this even matter? If the insight fuels an iteration and analysis of the problem the treatment solved for iPad users, then you are thinking like a scientist. But if you wish to use the finding to label your test a winner, you are grasping at straws.

- The ordeal doesn’t end there. Stats are a slippery slope, and the concept of “adequate power” isn’t widely understood. Often, testers celebrate “wins” that are clearly underpowered.

3. Running “safe” tests

The explore vs exploit debate is settled. Healthy experimentation programs maintain a balance between the two. In some cases, you may want to maximize the learning, while in others, going for immediate impact makes sense.

But the win-or-die mentality warps this dynamic. The desire to please stakeholders or avoid ‘failure’ often translates into an over-reliance on well-trodden ‘patterns.’ While not a huge red flag, this approach signals missed opportunities. Call it an orange flag.

Remember the example about surgeons? The one where surgeons who are judged by the survival rates of their patients feel compelled only to conduct safer surgeries, ignoring patients who need riskier operations? This is like that.

Yes, truly novel ideas carry higher risks, but they also open up new learning avenues.

4. Bypassing ethics

Another tell-tale sign that you’re too focused on the win is when ethics are getting compromised. One excellent example recounted in Goodhart’s Law and the Dangers of Metric Selection with A/B Testing is Facebook.

Their relentless focus on growth metrics, like active users and engagement, directly shaped their product and company culture. Teams tied to these KPIs were incentivized to boost those numbers at any cost.

This single-minded pursuit created a blind spot–vital concerns like the platform’s negative impact on society are neglected or actively downplayed.

In such an environment, ethical considerations take the backseat. The growth mandate often takes precedence even when internal research teams flag potential harm.

Sadly, we see unethical practices like p-hacking emerge as a grim extension of this ‘ends-justify-the-means’ mindset. Manipulated data and fudged reports become tools used to perpetuate the illusion of success and stave off scrutiny of a warped system.

Putting Mindless “Productivity” on a Pedestal

In experimentation, mindless productivity means running tests without a clear goal, neglecting long-term strategy, generating inadequate learning, and believing that the more tests you run, the better your CRO program is.

But what about Google, Booking.com, Microsoft, Netflix, and Amazon, which run thousands of tests each year? They have the most developed experimentation programs in the software industry, right?

It’s deeper than that.

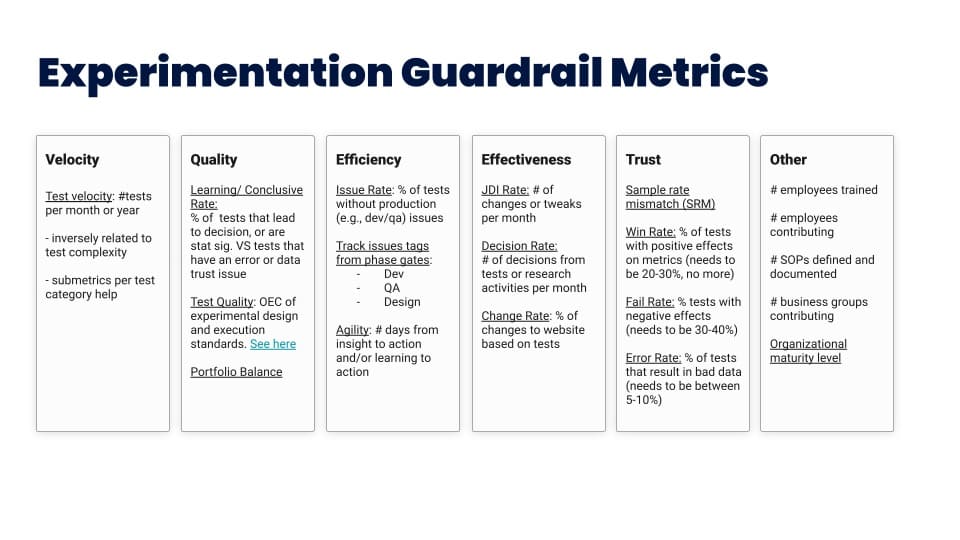

Yes, test velocity is a legitimate measure of your program’s maturity. But only when you look at it in the context of quality parameters like:

- Learning per test: How many experiments yielded valuable knowledge that informs future iterations or broader strategy?

- Actionable insights: Did the learnings translate into concrete changes that drive business results?

- Process optimization: Did testing reveal any bottlenecks or areas for improvement?

Shiva Manjunath shares a great example in this podcast episode, “If you run 50 button color tests a week, did you add value to the program?”

You did increase your velocity, and you can brag about the metric. But you did not improve anything of import, nor did you generate much learning.

When the quantity of tests is one of the main KPIs for a program, then the focus could be on doing a lot of experiments quickly, which might mean that they’re not well thought out or done carefully.

For example, the discovery/insight research could be rushed or incomplete. The ideation regarding the solutions as well. The outcome can be an inconsistent hypothesis/success KPI choice regarding the initial problem. When we do not take enough time to define the problem and explore a wide range of possible solutions, we can easily miss the point, only to launch as many campaigns as possible. This can also lead to partial dev or QA to ensure the test works properly.

Laura Duhommet, Lead CRO at Club Med

This is not to say test velocity is a lousy metric. No. We’re all familiar with Jeff Bezos’ quote, “Our success at Amazon is a function of how many experiments we do per year, per month, per week, per day…” Rather, test velocity makes more sense when weighed against the rate of insights generated.

Because as a measure of work done, not efficiency, test velocity alone is a vanity metric.

Matt Gershoff discusses how test type and design are often manipulated to inflate program output, rendering test processes ritualized for busyness and not necessarily for efficiency.

Another take on this, from the realm of product experimentation and development, is something Jonny Longden recently addressed in his newsletter.

Product teams are often measured solely on their ability to continuously deliver and ship features, but then they are judged based on the outcome of those features. This ends up with creative analytics, designed to show success from everything that is delivered, otherwise known as SPIN. This means they can meet their targets to deliver without bearing the consequences of the wider judgment.

Instead of focusing on increasing the number of tests you run, focus on increasing your velocity of learning. This may mean fewer tests, but if it means you’re learning faster, you’re on the right track.

11 Testers Share Their Clashes with Perverse Incentives

To better understand the ways warped metrics and misaligned goals distort the essence of experimentation, we’ve gathered insights from eleven testers. And we’ve grouped them under the two main types of perverse incentives:

Culture-Driven Perverse Incentives

Based on a deep-rooted ‘win-at-all-costs’ culture, where success is big lifts, this perverse incentive can pressure testers to compromise ethics and deprioritize rigor and process.

1. Focusing on uplift while ignoring critical metrics

This is common when conversion rates are viewed in isolation from other business health and success metrics. If this is present, something similar to the Facebook story above can happen.

The consequences can be so detrimental that they negate any benefits you gained from the uplift.

One notable example was a situation where the team was incentivized purely based on the uplift in conversion rates, ignoring other critical metrics like long-term customer value and retention. This led to short-term strategies that boosted conversions but had negative long-term impacts on customer satisfaction and brand reputation.

Tom Desmond, CEO of Uppercut SEO

2. Favoring quick success over a thorough learning process

Stephen Watts, Senior SEO and Web Growth Manager at Splunk, has witnessed the dangers of chasing immediate results in A/B testing. He highlights a common scenario–the premature declaration of victory.

The most common perverse incentives for A/B testing programs are (1) showing success and (2) doing so quickly. It’s simply the nature of A/B testing that most tests fail. Even for large programs with teams of data scientists and loads of traffic to test, most ideas for improving conversions and user behavior fail the test for mature websites.

It’s frequent to see A/B testers stop their test too early, as soon as their tool tells them they’ve got a positive result. By stopping early, they fail to learn that the test version would eventually normalize to the baseline level, and there isn’t a positive result.

Stephen Watts

Often, due to being pressured to secure A/B testing buy-in, testers feel a fundamental tension between rigorous experimentation and the need for quick, desirable results.

A team often tries to prove that an individual’s pet idea is a success. Whether it’s the idea of a HIPPO, other executive or the A/B testing team — people’s egos and internal politics often cause them to want to see specific results in the data, even if they aren’t really there.

A single A/B test can take months or years to achieve a result on many websites. This is even before replicating the results. Practically, no businesses are happy to sit around conducting a science experiment for a year just to find out if their conversions have slightly increased — all the while being forced to freeze the content and features on the tested areas. Not only does it make little business sense, but the results of such an extended test usually can’t be trusted because of the wide variety of outside factors impacting the traffic during that long single-test duration.

Stephen Watts

Inadvertent Perverse Incentives

While culture-driven perverse incentives in CRO are often blatant, the inadvertent ones can be most insidious.

The very design of your experiments can influence participant behavior in a way that challenges the integrity of your experiments. Here are some examples testers have observed:

1. Using tactics that attract the wrong audience or encourage superficial gains

Seemingly “good ideas” within experiments might generate undesirable behaviors that actively harm your goals.

Carrigan recounts a prime example of this phenomenon:

I’ve witnessed some real doozies in our A/B testing for marketing. The one that stands out to me most is when we offered free appraisals to generate leads, but homeowners who just wanted a freebie choked the funnel and displaced serious customers. I’ve talked with real estate agents whose use of certain Luxe language inflated bounce rates — the consensus here seemed to be that gourmet kitchens and granite countertops will attract affluent viewers. Still, it can also scare off middle-income buyers and, in turn, run the risk of shrinking your target audience.

Ryan Carrigan, Co-Founder of moveBuddha

‘Successful’ tests tend to boost your KPI, but they might mask deeper problems proudly sponsored by perverse incentives.

Like many brands, a brand I worked with offered a sign-up bonus to new customers to lure them into our app. Our sign-up rates increased exponentially, but the engagement levels were unaffected. Those sign-ups weren’t interested in our product but only in the offered bonus. We detected this discrepancy by regularly using data analytics and checking our engagement rates instead of the externally visible metrics.

We had to change our tactics to eliminate this issue. We associated the sign-up bonus with our desired action on the app: customers purchasing products through our platform. This approach incentivized potential customers who were not a part of our ecosystem while keeping away disinterested ones.

Faizan Khan, Public Relations and Content Marketing Specialist, Ubuy Australia

Andrei Vasilescu shares a personal example that highlights what happens when goals and testing methodology misalign:

We once tried a pop-up offering a $10 discount to get people to sign up for our newsletter. It worked too well—we got lots of fake email addresses because people just wanted the

discount, not our emails. It was like giving away treats for pretending to play guitar!

Andrei Vasilescu, Co-Founder & CEO of DontPayFull

2. Focusing on short-term engagement metrics over long-term user value

Metrics like time-on-site can give an illusion of higher user engagement. However, as Michael Sawyer notes, these metrics don’t translate into customer satisfaction:

A major example of this is tests performed by travel agencies where different customers are presented with destination options, where one group can be shown more choices than the other. […] While sometimes beneficial for data, this overabundance of choice yields poor user experience and customer loss. […] Stakeholders need to realize that while this strategy may offer short-term gains, it’s harmful to the business’s long-term health.

Michael Sawyer, Operations Director, Ultimate Kilimanjaro

Ekaterina Gamsriegler explains why such metrics can be misleading and produce a negative overall outcome:

Focusing solely on increasing user engagement metrics [with emphasis] on ‘depth,’ such as app session length, can lead teams to prioritize features that keep users in the app longer without necessarily enhancing the overall user experience. That’s why it’s crucial to delve into session data and conduct UX research to ensure that extended app sessions stem from genuine user value, not confusion or design issues. It’s also crucial to monitor the ‘breadth’ aspect of user engagement, e.g., average amount of sessions per user, app stickiness, long-term retention, etc.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler, Head of Marketing, Product Growth at Mimo

In Khunshan’s case, they introduced a gamification feature—virtual badges earned for sharing articles. However, the strategy quickly revealed its dark side:

We aimed to enhance user engagement on a news website through an A/B testing program. Introducing a feature where readers could earn virtual badges for extensive article sharing resulted in a surprising boost in engagement metrics. Users enthusiastically competed to collect more badges.

However, this apparent success came with unintended consequences, including a decline in the overall quality of shared content. Some users prioritized badge accumulation over sharing relevant or accurate information.

Khunshan Ahmad, CEO of EvolveDash Inc.

And here’s Ekaterina again with the analysis of gamifying your metrics, especially when those metrics are too far removed from their core contribution to your product’s success.

Gamification and instant gratification and popular ways to improve user activation and get users to the a-ha and habit moments. At the same time, when experimenting with adding too many gamification elements, one can find users focusing more on earning rewards rather than engaging with the app’s core functionality (e.g., learning a language), which can undermine the app’s original purpose.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler

But it doesn’t end there. Another way testers sacrifice long-term business health for short-term gains is by chasing click-through rates without considering their impact on conversion quality.

It’s essential to experiment with creatives that are relevant for your target audience and the context that the audience is in. However, making CTR the main KPI and pursuing an increase in CTR can lead to misleading ads with the primary focus on getting users to click on the ad. This can lead to a degradation of trust and user experience.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler

Jon Torres has seen this happen, and the outcome:

Focusing on click-through rates without considering conversion quality skewed decision-making toward flashy but misleading content.

Jon Torres, CEO of UP Venture Media

How to Detect Perverse Incentives

Detecting perverse incentives in A/B testing requires approaching the problem from multiple angles. Looking beyond surface-level metrics and carefully considering the long-term consequences of your treatments.

Ekaterina explains how you can take advantage of the common denominator of most perverse incentives (vanity metrics and short-term goals) to detect them in your experiments:

What perverse incentives might have in common is the focus on vanity metrics and short-term goals instead of deeper-funnel KPIs and long-term growth. With them, you can make progress with a metric at the bottom of your hierarchy of metrics but move the ‘higher’ KPIs in the wrong direction.

What I find very helpful is an experimentation template with a special section specifying:

– the primary metrics that you’re trying to improve

– the secondary metrics that you might see improving, even if they are not the target ones

– the guardrail metrics: the ones you need to monitor closely because hurting them would hurt the long-term outcomes and ‘higher’ level KPIs

– the tradeoffs: the metrics that might drop, and we’re willing to sacrifice them

Having a hierarchy of metrics built around your target KPI also helps to make sure that working on the lowest-level KPIs will lead to an improvement in the higher-level goals.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler

This describes an Overall Evaluation Criterion (OEC)—a holistic approach for assessing the success of a test that goes beyond focusing on a single metric and considers the overall impact on the business and its long-term goals. It:

- Broadens the scope beyond single, gameable metric,

- Aligns the desired outcomes with the overall business strategy,

- Tracks both intended and unintended consequences, and

- Evaluates the long-term impact of an experiment.

For instance, combining conversion rate objectives with customer satisfaction and retention metrics provides a more balanced approach. […] Aligning A/B testing goals with long-term business objectives avoids perverse incentives.

Tom Desmond

There’s a huge role leadership plays in making this happen:

And at the same time, acknowledge that no metric is going to be perfect, right? […] The challenge isn’t to find the perfect metrics, but to find the metrics that will help the teams execute in the short to medium term against the long-term objectives that the company has.”

Lukas goes on to say, “[Leadership should understand] their role in experimentation, how they play a part in enabling this. [Their part should not necessarily be] coming up with hypotheses and pushing for particular ideas. Part of the role of [leading for high-velocity experimentation culture] is giving teams a target to aim for [and] then monitoring their progress against that target. And when they start to go off the rails, to adjust the target. [Leaders should not] adjust by saying, “No, that’s wrong, you shouldn’t have run that experiment, that experiment is bad, you should stop doing that.” […] someone at the top should step in and say, “Actually, these metrics that we have set, they are causing perverse incentives, and so we should adjust the metrics so that the teams are actually optimizing for the right thing.

Lukas Vermeer in #216: Operationalizing a Culture of Experimentation with Lukas Vermeer

Another way to detect perverse incentives is by looking for what Ryan Carrigan calls “unexpected metrics.”

Don’t just track your leads and conversions. Track things like engagement times, bounce rates, and other qualitative feedback. Sudden shifts in these stats are a great way to identify likely unintended consequences.

Ryan Carrigan

Vigilance, continuous learning, and focusing on long-term value will help you avoid these hidden traps.

One key point is closely monitoring behavioral shifts that deviate from the intended goal. If individuals or systems respond in ways that exploit loopholes or achieve outcomes counter to the original purpose, it signals a perverse incentive.

For instance, if a pricing incentive meant to boost customer satisfaction inadvertently leads to deceptive practices, it’s important to recognize and rectify such discrepancies promptly. Regularly assessing outcomes against the intended objectives allows for the early identification of perverse incentives, enabling corrective actions to maintain alignment with the business’s overarching goals.

Nick Robinson, Co-Founder at PickandPullsellcar

We can also detect the impact of institutional perverse incentives by reviewing the backlog of test ideas. A team fixated on a single type of test, or one repeatedly favoring a particular location or audience, might be exploiting a ‘comfort zone’ of easy wins. This approach prevents actual exploration and is bound to exhaust once the local maximum is hit.

This isn’t nefarious per se. However, not all impacts of perverse incentives result in outright data manipulation.

Often sticking to this pattern of low-effort, low-risk tests may appear impressive to C-suite seeking quick ‘wins,’ but it puts a glass ceiling on more significant learning and bigger bets.

In the worst-case scenario, if promised results do not materialize yet everything is rosy on paper, you can be sure that the hard, gritty, frustrating science of experimentation has been disregarded, and perverse incentives are at play.

How to Manage Perverse Incentives

So far, we’ve explored the insidious nature of perverse incentives. We’ve seen how the pursuit of short-term gains can undermine long-term business health, distort metrics, and compromise customer experience.

While the challenges of perverse incentives are real, they can be minimized.

Yes, perverse incentives can happen, but that’s solvable with governance.

Ben Labay, CEO of Speero via LinkedIn Post

Let’s explore ways to manage perverse incentives in experimentation:

1. Align Test Ideas (and Metrics) with Business Goals

First and foremost, understand that your experimentation program cannot exist separate from the product, marketing, UX, and the business as a whole.

It is essential to clearly state the program goals and success KPIs and make sure they align with the different stakeholders’ goals (business, UX, product—not only business). We can also regularly check and update how we promote the program’s success to ensure it still makes sense regarding its goals.

Laura Duhommet

Speero’s Strategy Map offers a fantastic framework for this. It helps you zero in on specific growth levers (interest, acquisition, monetization, etc.) and the motions that drive them (marketing-led, product-led, etc.).

You want to make sure you are testing against metrics you need rather than the metrics you have. Think about what the right metrics are to prove the hypothesis, and if you find yourself not being able to test against them, then you have a problem.

Graham McNicoll in ‘Goodhart’s Law and the Dangers of Metric Selection with A/B Testing’

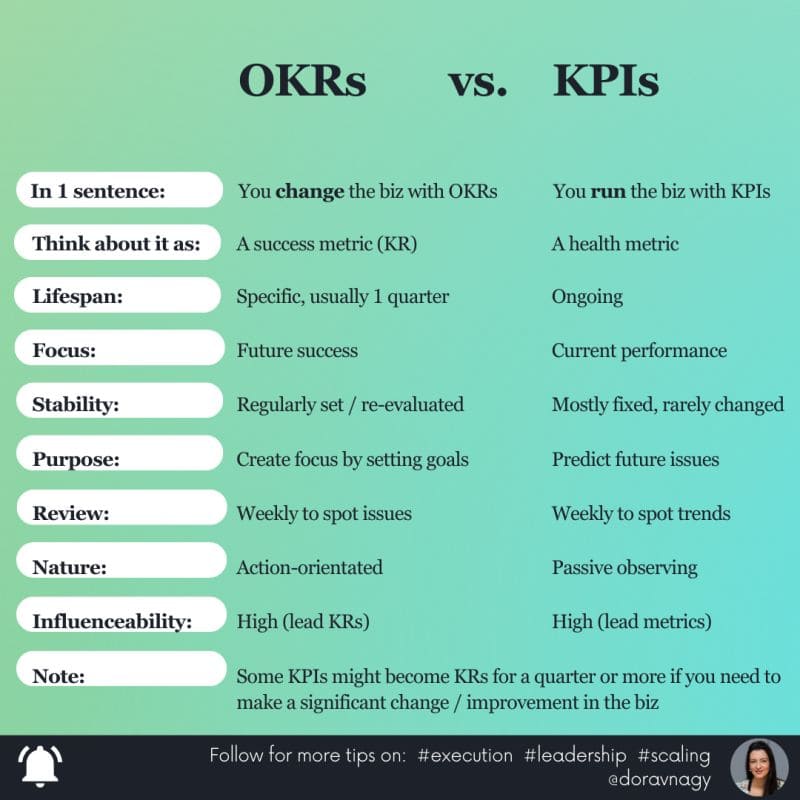

While you’re at it, remember that KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) aren’t the same beast. KPIs are the ongoing metrics you track, while OKRs are more ambitious, time-bound goals for the organization.

A word of caution: Even with the best intentions, your ‘growth map’ will need adjustments. As business priorities shift, your experimentation strategies must also adapt.

Regularly revisit your alignment to safeguard against inadvertently creating perverse incentives as your goals evolve.

2. Think Like a Scientist

Let’s get real: perverse incentives and scientific rigor don’t mix. It is almost impossible to chase quick wins while upholding the principles of experimentation.

True experimentation demands a commitment to sound methodology, statistics, and respecting the results—even when they don’t give you the ‘win’ you were looking for. There is no cherry-picking “positive” fragments from a failed test, no peeking at results mid-test, and no p-hacking to squeeze out a semblance of significance.

Monitor and ensure the hypotheses are as data-driven as possible and the problems are well-defined/reviewed with the most relevant people. This can be done with some simple “quality checks” regarding the test plans > hypothesis consistency, data sources and insights proof, test feasibility (Minimum sample size, MDE), etc.

Laura Duhommet

You’ve got to be brutally honest with yourself, your experimentation process, and the numbers.

Perverse incentives can mess with the quality of a program’s scientific method. […] It can encourage us to “play around with data” to get exciting results; optimizers might mess around with the data until they find something significant. This can give us false positives and make results seem more important than they really are.

Laura Duhommet

Some might argue that rigor is resource-expensive and slows down innovation. Here’s the thing: non-rigor is even more expensive; the cost just sneaks up on you in the form of incorrect conclusions or those subtle opportunities you miss because you’re only looking for big, obvious wins.

Rigor helps you:

- Maintain statistical significance, careful sampling, and bias reduction to ensure reliable results.

- Interpret data accurately, not just chase the numbers that make you feel good.

- See the true impact and potential risks so you make data-driven decisions.

- Scale what works and evolve as your business grows through thorough analysis.

Think of it this way: innovation without rigor is like a toddler let loose in the kitchen. Sure, they might create something “new,” but is it edible or even safe?

This is also the reason why legendary tester Brian Massey wears a lab coat. A/B testing is science.

3. Foster a Culture where Everyone Can Call Out Perverse Incentives

Perverse incentives thrive in the shadows. So, you must break down silos:

With more visibility on experiments within your organization, you’ll have increased vigilance against misleading metrics.

We promote a deeper understanding of the importance of ethical and sustainable optimization practices by presenting scenarios where alternative strategies could yield better results in immediate metrics and overall business health.

Khunshan Ahmad

Share those experiment results with all departments and teams. Don’t limit insights to just the testing team. Circulate your findings and educate colleagues across the organization through in-house programs, such as a dedicated Slackbot that shares experimentation facts, a weekly newsletter, and monthly town halls.

Additionally, sharing the results of every experiment with the rest of the organization in a dedicated communication channel (e.g., Slack) allows for constructive feedback, helping refine conclusions and ensuring the entire team moves forward with a holistic understanding.

Ekaterina Gamsriegler

Bring in agencies or outside experts for workshops on solid experimentation basics, and use transparently shared scorecards to keep everyone in the loop.

When communicating perverse incentives, I tend to emphasize education. Highlighting the problem alone will only cause tension. It’s important to approach the conversation prepared to suggest alternative A/B tests or marketing strategies. Acknowledging pitfalls and actively seeking solutions is a surefire way to foster trust and guarantee that your marketing serves its best purpose.

Ryan Carrigan

Encourage questioning, not blind acceptance. This signals that it’s safe to challenge assumptions and point out potential flaws in strategies.

Stay humble and be ready to adjust if something’s not working. Make sure that the program and the product are continuously improved, with continuous training, monitoring stakeholders’ opinions, program success, fostering a culture that values learning from mistakes and always seeks improvement, etc.

Laura Duhommet

This open dialogue will not only boost buy-in for experimentation, but it will turn everyone into perverse incentive detection sensors—just like the distributed awareness encouraged by Holacracy.

To solve these [perverse incentives] issues, A/B testing teams must teach their stakeholders what is and isn’t appropriate to test. Teams—if they have the traffic—often shouldn’t be testing small changes on a single webpage, trying to achieve a 1 or 2% gain. They should look for radical changes that break out of the local maximum. Testers should be running experiments across not just one or two web pages but entire website sections, across hundreds or thousands of pages at once in aggregate where possible to increase the sample size and lower the test duration.

Stephen Watts

Get input from people who don’t directly benefit from the outcome of experimentation. Often, those with a less vested interest can pinpoint perverse incentives that those intimately involved may overlook (sometimes unintentionally!).

It can also help to stay open about experiment decision-making and encourage people who are really interested to share their thoughts, especially those who might not directly benefit, to avoid confirmation bias of the optimizers.

Laura Duhommet

Remember: Cultivating this proactive culture takes time and consistent effort. But the payoff is huge: a team empowered to call out problematic metrics before they cause damage, fostering true innovation rooted in reliable data.

4. Create Psychologically Safe Experimentation Programs

It turns out that the battle against perverse incentives isn’t just about metrics and test setups—it’s about creating an environment where people feel empowered to take risks, learn from setbacks, and prioritize true progress.

Lee et al. (2004) found that employees are less likely to experiment when they face high evaluative pressure and when the company’s values and rewards don’t align with supporting experimentation.

For example, inconsistent signals about the value of experimentation and the consequences of failure would discourage risk-taking and innovation, even if the organization officially and vocally supports these activities.

This could lead to a scenario where employees are motivated to play it safe and avoid experimentation.

Just saying you don’t mind people failing experiments doesn’t make people feel that’s really true.

This means rethinking how you incentivize your teams and how you respond to experiments that don’t yield the expected outcome.

When we find a problem, we don’t just sound the alarm. We explain what’s going wrong in a way everyone can understand. We show how these tricks can mess up our plans and suggest better ways to test things. It’s important to talk clearly and not just blame people.

Perverse incentives aren’t done on purpose. They’re like hidden traps. To avoid them, we need to talk openly, really understand our data, and always think about our long-term goals. This helps make sure our tests actually help us instead of causing problems.

And here’s some interesting info: 70% of A/B tests can be misleading. Tricks like perverse incentives cost companies a ton of money—about $1.3 trillion a year! Companies that really get data tend to make more money. Talking well with your team can make people 23% more involved in their work. Being trustworthy makes customers 56% more loyal. So, using A/B tests the right way, with honesty and care, can really help your business grow without falling into these sneaky traps.

Andrei Vasilescu

5. Run an ‘Experimentation’ Program Instead of a ‘CRO’ Program

Words matter. Language defines culture—the way we think and act—and lays the foundation of success.

The term “Conversion Rate Optimization” itself carries baggage—an obsession with a single metric, a short-term focus on a downstream metric that is well nigh impossible to control.

It is also going through the same commoditization phase SEO went through, where companies can choose to do “some CRO” before a launch and expect to reap the rewards. It’s all about the revenue.

Experimentation, though, is human nature. It’s how we learn, grow, and innovate. It’s a constant part of our daily life and thought processes.

Framing your efforts around this concept shifts the focus from desperate outcome-chasing to a structured yet exploratory process. This emphasis on process protects you from the trap of perverse incentives.

Sell experimentation as a low-barrier innovation enabler. Then, ensure that those who execute understand that the quality of the input defines the program. That it’s not a magic revenue bullet.

But hey, that’s easier said than done. You’d have to change:

- What metrics are tracked

- How performance is measured, and

- How buy-in stays secured.

You may even have to re-think compensation for the experimenters.

But once we achieve this pivot, the payoff is massive. The potential perverse incentives are now golden incentives, encouraging forward thinking, consideration of long-term impact, big bets, and high-quality ideation.

Conclusion

Let’s close out with this from Kelly Anne Wortham:

Many experimentation SMEs and platforms focus all their time on metrics—specifically—the conversion rate. Like I said in my response — we even let ourselves be called CROs (at least some do. It’s a case of Goodhart’s law where the measure has become the target; it ceases to be a good measure. We are focusing on converting customers instead of understanding customer pain and working to truly resolve those pain points with true product solutions and improved usability. The end result is the same (higher conversion), but the focus is wrong. It feels like our goal shouldn’t be to improve conversion rate but rather to improve decision-making and customer satisfaction with the brand. And perhaps there’s a way to show that we are informing product changes with research and experimentation that is supported by customer empathy. All of these things would be more closely linked to our actual goal of building a better relationship between a brand and its customers. Which, at the end of the day, will increase the conversion rate.

Kelly Anne Wortham, Founder of Test & Learn Community (TLC)

References

De Feo, R. (2023). The perverse incentives in academia to produce positive results. [Cochrane blog]. s4be.cochrane.org/blog/2023/11/06/the-perverse-incentives-in-academia-to-produce-positive-results/

Dufner, M., Gebauer, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019). Self-Enhancement and Psychological Adjustment: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personality and social psychology review: an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc., 23(1), 48–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318756467

Lee, F., Edmondson, A. C., Thomke, S., & Worline, M. (2004). The Mixed Effects of Inconsistency on Experimentation in Organizations. Organization Science, 15(3), 310–326. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30034735

Mattson, C., Bushardt, R. L., & Artino, A. R., Jr (2021). “When a Measure Becomes a Target, It Ceases to be a Good Measure.” Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 13(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-20-01492.1

Robins, Richard & Beer, Jennifer. (2001). Positive Illusions About the Self: Short-Term Benefits and Long-Term Costs. Journal of personality and social psychology. 80. 340-52. 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.340

Written By

Uwemedimo Usa, Trina Moitra

Edited By

Carmen Apostu

Contributions By

Craig Sullivan, Ekaterina Gamsriegler, Jonny Longden, Kelly Anne Wortham, Laura Duhommet, Ryan Carrigan, Shiva Manjunath, Stephen Watts